Ethics for the Common Man

We may well complain that our generation ranks among the most immoral generations of history and that could well be true. But the more sinister issue is the reason that lies behind this tragedy. It is the fact that ours is probably the most amoral generation of history. It simply does not possess any meaningful framework of morals to guide its conduct. To borrow the overused cliché, ‘It lacks a moral compass’. People behave the way they do because morally and spiritually, as in the days of Jonah’s Nineveh, ‘they cannot tell their right hand from their left’ (Jon 4.11). This does not mean they are less culpable for their conduct, but it does explain the recklessness of their actions.

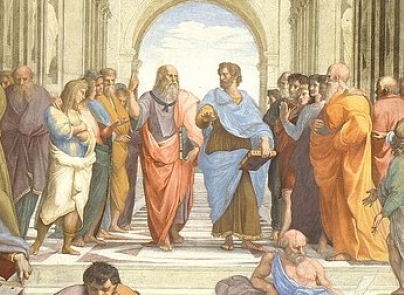

In one sense this state of affairs is inevitable, given the evolution of Western philosophical and scientific thought ever since the Enlightenment. By exalting humanity and reason to a self-referential status, we have made ourselves the measure of everything. We have chosen to ignore all external co-ordinates that may (and do) have a bearing on how we make sense of our world and what we do with our life in that world. So the problem of the human condition is understood only from within its own problematic perspective. Not surprisingly, therefore, every attempt by liberal humanism to produce a code of ethics is self-contradictory and ultimately self-defeating.

Sadly the church is not immune from this problem. Every convert brought into the fold of the church from without brings his or her baggage from their morally disorientated past, none of which is easily left at the door. But, more than that, for a generation and longer, the church has seen a generation of its own being increasingly shaped by a world that no longer believes in moral norms and which itself no longer has an innately Christian moral framework. How then should it respond?

It would be tempting to say it simply needs to get back to God’s law in the Ten Commandments. And that is surely true, but not in some crass mechanical sense. To view the law – even God’s law – in detached isolation will at the very least lead to its being misunderstood, but also to its being distorted and abused. After all, the Pharisees and experts in the law of Jesus’ day were ‘law men’ par excellence, but were anything but commended by Jesus as the supreme lawgiver.

It is interesting, therefore, that Jesus re-presents the law of God in the Sermon on the Mount he does so in a way that reminds his hearers – in line with its Mosaic manifestation – that the law of God must always function in the context of our relationship with the God who gave it. So as we follow the contours of his exposition and application of that law, it is fascinating to see how, both individually and corporately, the lives those who submit to God’s rule through it are beautifully reconfigured. If we take a high altitude overview of this most famous sermon, we see how these features stand out.

In the first place through lives that are attractively different. Christians and churches know that they should be different, but too often they are simply odd, even verging on weird. When Jesus uses the language of blessedness in this opening section he is not only speaking of the blessedness experienced by his people, but is also inferring that they will be instruments of blessing to all whose lives they touch. Benediction is a thing of beauty.

In the second place, such a life will inevitably provoke reaction – even to the point of persecution. Again this should not surprise. The presence of beauty will expose what is ugly. The beauty and purity of Christ provoked the worst reaction this world has ever seen as his light invaded its darkness. Those who live by the code of the Kingdom will arouse the hostility of those who are its enemies.

Tied to this, thirdly, is a morality that is not superficial. With the morality of the ‘law men’ of his own day very much in view, Jesus addresses commands that relate to murder, marriage and honesty. With a striking economy of words, he exposes the hypocrisy bound with the Pharisees’ interpretation of these laws – something that was more about preserving their own interests rather than the good of others and the glory of God.

The same is true in the next strand in Jesus’ exposition in which he speaks of justice tempered by mercy. Over against the lex talionis approach favoured by the legal rigorists he advocates an utterly countercultural way to seek justice. By ‘turning the other cheek’ and by freely offering a second item of clothing when coerced into giving one. Such an approach to law is not self-protective, but God-reflective.

When it comes to the law and religious observance through giving, prayer and fasting, our Lord describes a piety that is not plastic. Service to God and others that is not about creating impressions, but living out a genuine reverence for God, reliance on his promise and respect for our fellow men.

As he shifts from worship to wealth in the sixth segment of this sermon on kingdom life, Jesus opens up both the depths and the heights to which this life reaches. Treasure in heaven that has a stronger hold on us than its earthly counterparts and trust in God that burrows right down into even the most mundane issues of daily life.

The seventh facet of this life on earth that is shaped by the ethics of heaven is that it will be humble, trusting and courageous. Humble because it is more conscious of its own log-like failings than the peccadillos of others. Trusting because it knows that although our asking, seeking and knocking will not always be met with an immediate response from God, we rest in the knowledge that our Father in Heaven is committed to giving the very best. And courageous because it is willing to go through gates and follow roads that are less well travelled, but which ultimately lead to life.

The crowning feature of this beatified life is that its genuineness is proved over the long haul and it survives the tests of time. Mixing metaphors, Jesus speaks of healthy trees that produce good fruit and deep foundations that are not washed away in storm and flood.

An ethic that is no more than rules and regulations is wooden; but this kingdom ethic bound up with the life of the kingdom that is both beautiful and beneficial. Such an ethic is not the preserve of a self-serving religious elite; it is truly for ordinary people in all kinds of life situations.