Where’s the Love? Polanus on Divine Goodness

What is essential in an adequate list of Divine attributes?

Summarizing the attributes of God is a difficult task, and hardly two lists of divine attributes agree. In this light, many people have asked, “Where is the love of God in the Westminster Shorter Catechism?” The fourth question describes God as “a Spirit, infinite, eternal, and unchangeable in his being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness, and truth.” If the Scriptures say, “God is love” (1 Jn. 4:8), then is it not irresponsible to omit love from a list of divine attributes?

It may be helpful to readers to understand the interrelationship between the divine attributes in the context of the Westminster Assembly in order to know where love fits. When understood in context, the relationship between divine goodness and divine love shows that love is still present in the Catechism by implication.

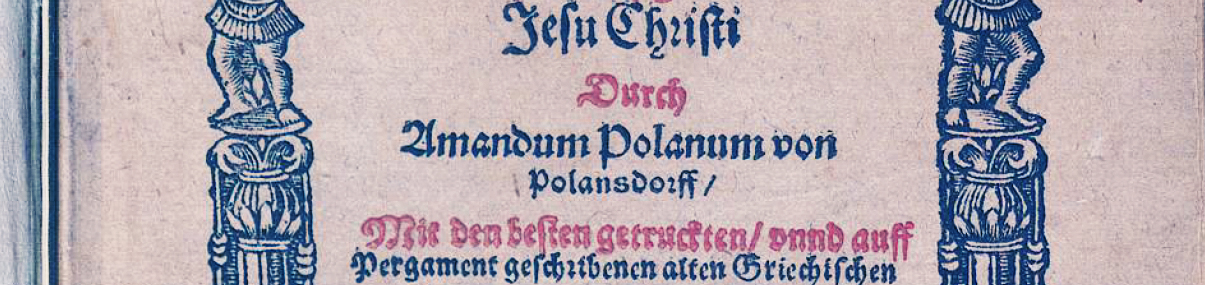

Amandus Polanus illustrates how older Reformed authors tended to treat divine love as flowing from divine goodness. While his position was not unique, his treatment of it is both clear and helpful for understanding the relationship between the divine attributes and how these ideas found expression in the Shorter Catechism. Even if readers do not end up agreeing with him at every point, his material can only help to understand the perspective of older Reformed theology on this point. This can help us better assess our understanding of the interrelationship of the divine attributes today as well.

Polanus opened his treatment of the relationship between divine goodness and love by citing Jerome Zanchi. Zanchi wrote that the goodness of God is the fountain of the grace, love, mercy, patience, and clemency of God (“Bonitas Dei est fons gratie, amoris, misercordiae, patientiae, clementiae Dei;” 1039). Polanus then added that the goodness of God is, in order of nature, prior to the grace, love, mercy, patience, and the clemency of God. The basic assumption behind these connections seems to be that goodness is an absolute divine attribute, while love is a relative one.

Modern readers who are unfamiliar with these terms should understand that this does not mean that God is identical with some of his attributes, yet not others. Instead, it means that his essential properties express themselves in particular ways relative to creation. Thus, justice is an essential attribute, while wrath is justice expressed in relation to–or relative to–sinful creatures. Polanus continued by arguing that the goodness of God’s nature gives birth to grace along with all of the other attributes that he lists (1039). He added that this was why Psalm 117 placed goodness first, then mercy, so that we might understand that goodness is the fountain of mercy. So it is with divine love. He noted that Titus 3:4-5 placed goodness and love in a parallel order and that this order was intentional (1040). In his view, in other words, the Bible treated goodness as a broader category than mercy and love. In addition to these statements about goodness, he concluded by saying that love proceeds from grace, mercy proceeds from love, and clemency and patience proceed from both of these. Goodness was thus a wide category that included grace, love, mercy, patience, and clemency.

This does not demean love as a divine attribute as much as it recognizes divine simplicity and the fact that divine attributes primary help us make distinctions in talking about God instead of importing real distinctions into his nature or essence. This does not mean that his attributes are only empty names, but it does mean that they express various facets of the character of a unique Being that mutually inform and imply one another.

The Westminster divines intended the Shorter Catechism to be a concise summary of Christian doctrine. This means that they intended to include as many things as they could in the fewest words. In their minds, this meant that love was included under goodness. This did not mean that love was not integral to the divine nature. God is love, and God is all of his attributes. Whether we agree with the idea that love is subsumed under goodness or not, it should at least comfort us (and ease the consciences of some) to know that love is still included in the Catechism.

Perhaps it would be better to treat love as an absolute rather than a relative divine attribute because love begins with intra-trinitarian love, rather than with the inherent goodness of the Creator spilling over into God’s relation to his creatures. In either case, we should remember that God’s goodness is gracious, loving, merciful, patient, and kind. Likewise, his love is good, and harmonizes with all of his other attributes. God always does what he does because he is who he is and he is never only partly himself in anything that he does.

We will always struggle to speak adequately about God’s attributes. We should not neglect any of them. Yet we should also be charitable and try to understand why our forefathers expressed themselves the way that they did and we should imitate their devotion to the good God who is love.

Ryan McGraw (@RyanMMcGraw1) is associate professor of Systematic Theology at Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Greenville, South Carolina.

Related Links

“A Cross-Shaped View of God’s Attributes” by Aaron Denlinger

The Attributes of God by A.W. Pink

Divine Simplicity, edited by Jeffrey Stivason [ Print Booklet | PDF Download ]

PCRT ’87: How Great Thou Art [ Audio Disc | MP3 Disc | Download ]