Juan Pérez de Pineda and other Spanish Reformers

Juan Pérez de Pineda and other Spanish Reformers

In Spain, Martin Luther’s message met the immediate and fierce opposition of both the Roman Catholic Church and the Spanish rulers, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. To repress it, they had already a powerful tool at hand: the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, established in 1478 primarily to identify false converts from Islam and Judaism. This institution became particularly active after 1492, when the Spanish forces defeated the last Muslim stronghold in Spain, the kingdom of Granada.

Soon, this court became especially strict and cruel against anyone who believed anything different than the church of Rome. If those who had embraced the teachings of Luther wanted to save their lives, they had to flee the country. But the Spanish authorities didn’t let these escapes go undenounced. They made life-size puppets that looked like the fugitives and burned them in a public square as a warning to others.

Pérez’s Studies and Exile

One of these fugitives was Juan Pérez de Pineda, a native of sunny Andalusia. Nothing is known of his early life. After taking religious orders and earning a doctorate, he entered in the service of Emperor Charles V in Rome, where he lived through the Sack of 1527. There, he was apparently connected with Alfonso de Valdés, brother of the Reformer Juan de Valdés. Both Alfonso and Juan were part of the Alumbrados, a group of believers who sympathized with Erasmus and Luther in their desire to reform the church.

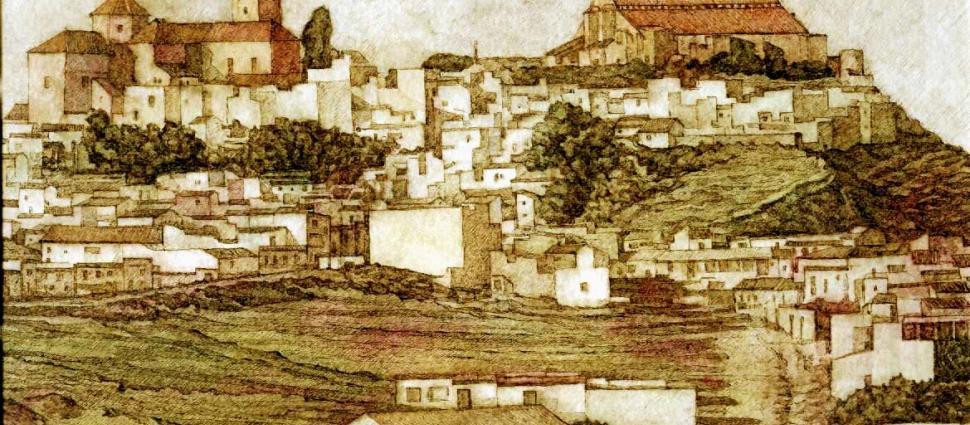

Eventually, Pérez returned to Spain, and settled in Seville, where he taught in the city’s orphanage, the Collegio de los Niños de la Doctrina. By then, Seville had become a hotbed of Reformed discussions, which couldn’t escape the vigilant eye of the Inquisition. Around 1549, the Inquisition arrested the city’s bishop, Juan Gil (also known as “Doctor Egidio”) for his involvement in these discussions and his “suspicious” sermons. Egidio was eventually tried and locked in a prison where he died in 1555. In 1560, his bones were disinterred and publicly burned.

Pérez was not there to witness this public display. As many other Spaniards, he took Gil’s arrest as a sign that it was time to leave Spain, and fled to Paris with two other priests who worked at the same orphanage: Luis Hernández del Castillo and Diego de La Cruz. In Paris, they shared a house with Juan Morillo, who had recently been present at the Council of Trent in the entourage of Cardinal Reginald Pole. Unlike Pole, who decided to subordinate his convictions on sola gratia to his loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church, Morillo had taken a risky stand. Morillo and his friend continued to read Protestant works and kept their doors open to other like-minded people.

Peréz’s Writings

From Paris, Pérez moved to Geneva, where he began the most influential work of his life: the translation of the New Testament, the Psalms, Calvin’s catechism, and a few other Protestant books into Spanish. He also wrote a letter to encourage other Spaniards who suffered under the Inquisition, and a letter to the Spanish king Philip II, asking him to stop the persecution.

By that time, the persecution in Spain was intense and relentless. Many of the accused were publicly burned, often after being tortured or publicly flogged and dragged through the streets of their cities. No one was beyond suspicion. Even Archbishop Bartolomé Caranza, the highest religious authority in Spain, was arrested on charges of heresy for having used a text by Melanchthon in preparing a presentation for the Council of Trent, and for holding some books by Luther and Calvin in his library.

In his letter, packed full of Scriptures, Pérez encouraged the Christians in Spain to remember their high privilege of serving the King of kings, and to place their trust in God rather than men. He exhorted them to remain faithful, looking unto Jesus “our victory,” and to the final welcome they will receive into his kingdom.

Pérez’s translations were smuggled into Spain, largely through a devoted messenger named Julian Hernandez (also known as Julianillo because of his short stature). According to traditional accounts, Juanillo dressed as a merchant in order to transport Spanish Bibles into Spain by mule, hidden inside barrels. He was finally betrayed, arrested, and tortured before his execution by burning. Pérez was also condemned by the Spanish Inquisition and his effigy was publicly burned in Spain.

Later Years and Legacy

Around 1556, Pérez was sent with Calvin to Frankfurt in a conciliatory mission, and remained there until 1558, when he signed the Frankfurt Recess, an attempt to bring unity to the Lutheran understanding of the Lord’s Supper. After this Pérez returned to Geneva, where he continued his ministry as translator, writer, and pastor of a Spanish congregation.

In 1562, he resigned from his post because of ill health. Once he recovered, he moved to France in response to a call for pastors. In 1564, he became domestic chaplain for Renée of France, in her castle at Montargis. He continued to revise his translations and supervised their printing in Paris. He died in 1566. Before dying, he left all of his goods for the printing of the Bible in Spanish.

Eventually, the French authorities seized his works and burned them, but parts of his translation of the New Testament were incorporated into the Spanish full Bible published in 1569 by Casiodoro de la Reina, a former monk and fellow exile, who availed himself of Pérez’s inheritance for this work. In the 19th century, literary critic Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo considered Pérez’s translation of the Psalms the best of all.

Today, Pérez is still remembered and appreciated in Spain, especially in evangelical circles, and a street in Seville is named after him.