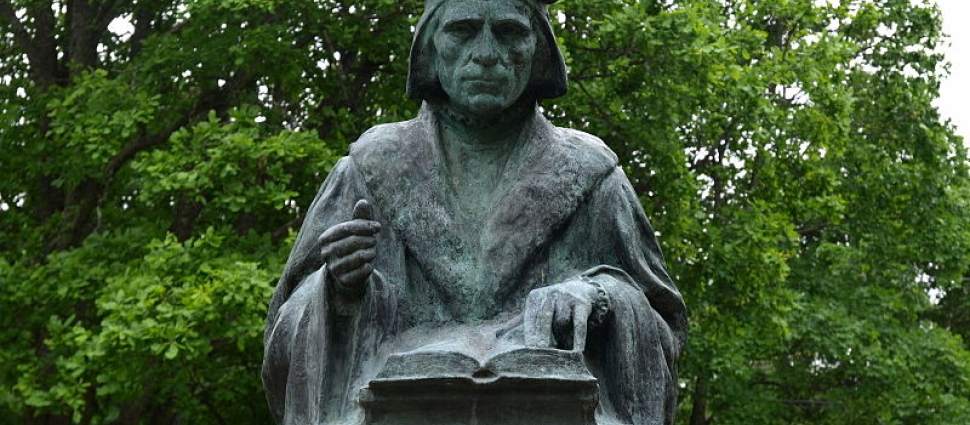

Mikael Agricola and the Reformation in Finland

Mikael Agricola and the Reformation in Finland

Like Primoz Trubar in Slovenia, Mikael Agricola was a Protestant reformer who had to develop a language before he could spread the gospel.

From Farmer to Bishop

Born around the year 1509 in a small village on the southern coast of Finland, Agricola (originally Mikael Olavinpoika - “son of Olavi”) was able to receive a humanist education in Viipuri (or Vyborg, now in Russia), under Johannes Erasmi. It was there that he adopted the Latin name Agricola, meaning “farmer” (his father’s occupation).

In 1528, Martin Skytte, a Dominican prior who was newly appointed to the bishopric of Turku (a major Finnish town), invited Erasmi to work as his secretary and Agricola as his scribe. When Erasmi died the following year, Agricola took his place.

The same epidemic that took Erasmi’s life struck Petrus Särkilahti, a preacher with Lutheran leanings who had been proclaiming the gospel in Turku since 1523. Agricola benefited from Särkilahti’s preaching and studied some of Luther’s works. In 1530, he was ordained priest and preached both in Turku and other cities.

While still a Roman Catholic, Skytte agreed with Luther’s doctrines of grace and held the University of Wittenberg in high esteem, so much that he sent eight of his young priests, including Agricola, to study there. While in Wittenberg, these men worked on a translation of the New Testament from Greek into Finnish.

Agricola stayed in Wittenberg from 1536 to 1539 when, provided with a letter of recommendation by Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, he returned to Turku and became headmaster of its prestigious cathedral school. This was not a dream job. The students were often unruly, getting into fights and bringing mayhem to the city, while the teachers’ salaries suffered from frequent cuts.

In spite of this, he found it hard to leave his position when King Gustav Vasa (ruler over Sweden and Finland) replaced him with another headmaster. Agricola then continued to serve as assistant to the bishop. When Skytte died in 1550, Agricola became a de-facto bishop, even if the his seat remained officially open for a few years, waiting for the king’s orders. In the meantime, Agricola suffered, like most of the Finnish people, from the effects of a dreadful famine. He was appointed bishop in 1554, becoming Finland’s first Protestant bishop.

As it had been for over a thousand years, bishops had to take on the task of mediators and problem-solvers for the people in their area. Agricola’s region was particularly unstable, with frequent uprisings and riots. At one point, the unrest became so severe that he had to furnish a priest with four farmworkers and three German shepherds to work as his bodyguards.

The king also expected Agricola to help him in negotiating with Russia over the uncertain borders between the two countries. It was a difficult duty, which required much wisdom and patience.

Formalizing a Language and Preaching the Gospel

Today, Agricola is mostly remembered as the father of Finnish orthography and literature. His work in this area was essential in order to provide the Finnish people with written texts in their language (which was only spoken).

His first publication (around 1543) was an alphabet book (Abkiria). This was also the first published book in the Finnish language. It was followed, two years later, by a 900-page Prayer Book – a collection of prayers taken mostly from the Bible, with the addition of others by some church fathers and Lutheran reformers. He also included a short calendar with notices of particular interest to farmers (related to weather, astronomy, and hygiene). These two books became popular in Finnish homes and encouraged family study and prayer.

The translation of the Finnish New Testament was completed in 1543 and published in 1548. Agricola did much of the work of translating and editing, and added his translation of some prefaces and explanations by Luther (such as his preface to Romans). This doesn’t mean he took all of Luther’s writings, lock, stock, and barrel. He included his own thoughts, wrote his own prefaces, and edited portions which didn’t apply to Finland.

He also translated parts of the Old Testament, and completed and perfected some translations of the Psalms that were previously done in Turku. Other translations included works on liturgy of the Swedish reformer Olaus Petri.

Some of his works include an account of the previous pagan religions of Finland and the subsequent Christianization. These have been very important for historians.

In introducing the Reformation to Finland, Agricola followed Luther’s example of moderation, aiming at explaining the changes rather than forcing them on the population. For example, he included in his Prayer Book the Ave Maria, but only as angelic salutation and song of praise about what God had done. He emphasized this with a strong warning against looking for mediation between God and humanity in anyone but Christ.

In 1554, war broke out between Russia and the Kingdom of Sweden-Finland. Two years later, King Vasa sent a delegation to Russia, which included 48-year old Agricola, to discuss a possible peace treaty with Tsar Ivan the Terrible. Ivan made the delegation wait, then moved the talks to another city. Once a treaty was reached and confirmed, the delegation returned by sled and boat in freezing cold weather. This trip proved to be too stressful for Agricola, who died in 1557, soon after reaching Finland.

April 9, the day of Agricola’s birth, is celebrated in Finland as Day of the Finnish Language (ranked as one of the most difficult languages in the world).