Socinianism: Then and Now?

The term "Socinianism" has recently appeared in various theological discussions, especially as it relates to topics such as the doctrine of the Trinity and biblicism. At the same time, many have little familiarity with the history or definitive marks of Socinian thought. This is in part due to the fact that our only interactions with Socinianism are found in their interlocutors (e.g. Francis Turretin). As a result, the term itself can at times serve as a convenient strawman, stuffed and dressed to resemble the theological position of one's opponent.

In this article, I'd like to show some of the distinctives of Socinianism and its broader influence, with a concluding thought on whether there are Socinians today. My hope is that those unfamiliar with the subject will be helped and able to further engage in fruitful dialogue.

What is Socinianism?

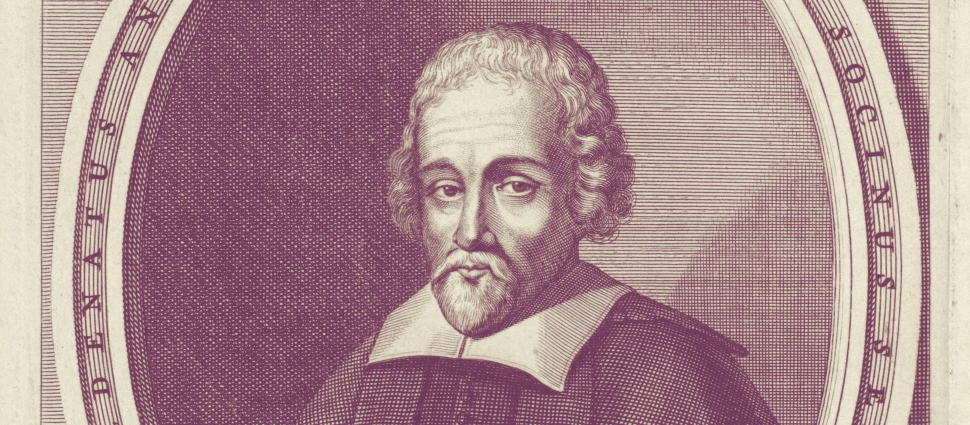

Taking its name after two Italian theologians, Laelius and Faustus Sozzini (Latin: Socinus), Socinianism was an anti-Trinitarian belief system that came about during the time of the Radical Reformation of the 16th century. Faustus came from a long line of Italian jurists and was heavily influenced by the writings of his uncle Laelius. Laelius himself had interacted with many Reformers, but ultimately rejected the doctrines of the Reformation.[1] This family history, coupled with a growing antagonism towards Catholicism, resulted in Faustus' radical departure from the theological approach of the Reformers, culminating in the publication of the Racovian Catechism in 1609 (five years after his death).

According to William Cunningham, Socinianism can be defined as

“... [a] rationalistic perversion of the true principles of the Reformation, as to the investigation of divine truth and the interpretation of scripture…the making of human reason, or rather men’s whole natural faculties and capacities, virtually the test or standard of truth.”[2]

For Socinus, this meant a fundamental rejection of traditional Christian truths that were confessed for centuries. The Socinians were not simply quibbling over adiaphora; they denied the doctrine of the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, the need for an atonement, and the inspiration and infallibility of Scripture.

Ironically, though they denied the inspiration of the Scripture, they sought to take the bible seriously. According to Cunningham, the Socinians “admit that the teaching of Christ is, in the main, and as to its substance, correctly enough set forth in the New Testament; and they do not allege that it can be learned from any other source.”[3] Rather than looking for guidance in the creedal tradition of the church passed down through the ages and affirmed in the Reformation, Socinians believed that only the Bible could be appealed to in matters of faith. In other words, Socinians were the strict Biblicists of their day, rejecting any non-biblical source and seeking to derive all beliefs from Scripture alone.

Johan Crell

In 1631, Socinian theologian, Johan Crell published an influential work, entitled De Uno Deo Patre. In this work, Crell rejected the distinction between person and essence found in Trinitarian works, insisting that “it was impossible to make any sense of the doctrine of the Trinity within the Aristotelian categories used by academics. However one sought to explain it, absurdity would soon follow, for the metaphysical framework used by theologians to explain and interpret the Trinity was itself incoherent.”[4] Thus, the rejection of metaphysics led the Socinians to reject necessary doctrines, such as the classical and accepted doctrine of divine simplicity.

Crell rejected traditional metaphysics that were present in and agreed upon by the church in favor of a Biblicist hermeneutic that sought to show that Christ wasn’t coequal with the Father, but that “God had, however, chosen to delegate some of his authority and sovereignty – not his essence – to Christ” in hopes that his readers would see his view as “much more coherent than the orthodox description of him as co-essential with the Father.”[5] His Biblicist approach and rejection of traditional categories led him to deny key articles of the faith, thereby denying the faith once for all delivered to the saints (Jude 3). Yet, their beliefs were not simply a denial of fundamental Christian truths and hermeneutics, but they had “their own doctrines regarding them, which are not mere negations, but may be, and are, embodied in positive propositions.”[6] It wasn’t simply that they denied Aristotelian metaphysics as adopted by the church, but they positively put forth their own view. They didn’t simply deny the distinction between essence and person, but they positively stated their uniformity.

Socinian Influence

The problem of Socinianism was not isolated to one place or movement, but their influence was felt among groups like the Remonstrants, who also rejected key metaphysical categories and historical doctrines. Only those things explicitly found in scripture could were of first order, and anything that depended upon philosophy or outside sources was disputable. Simon Episcopius rejected the orthodox doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son because, according to him, these doctrines and categories were completely absent and unknown to early Christians.[7]

Thomas Hobbes, one of the most influential thinkers in all of history was also possibly influenced by Socinian thought. Although he did not deny the Trinity, he agreed with the Socinians and Remonstrants in rejecting scholastic metaphysics, causing him to throw out historical Creeds, such as the Athanasian Creed, in favor of a redefinition of the Trinity according to his own ends.[8] Even if Thomas Hobbes was not directly influenced by Socinianism, it cannot be denied that much of what drove his conclusions were similar to Socinian thought. If Hobbes were alive today, perhaps we would label him a “semi-Socinian”[9] or “neo-Socinian.”

Socinianism Today

Are there Socinians today? The short answer is yes. There is a close relationship (both theologically and historically) to Unitarianism. Although not fully Socinian, Mormonism bears some of the marks of Socinian thought, especially as it pertains to their doctrine that God, being a person, has a physical body. Indeed, there are people who, seeking to be faithful to scripture, reject the Trinity and other key doctrines because they find them incompatible with the Bible and reason. Although not a major movement as such (you’re not going to walk into First Socinian of such and such town any time soon), the thought and conclusions of the early Socinians are still around.

Perhaps more pertinent to the Evangelical church today, is the rise of what some have called “Neo-Socinianism” in recent years. This label comes from the growing trend among theologians who, much like the Socinians, reject the classic doctrine of God and are hostile towards Aristotelian metaphysics, especially as articulated by Thomas Aquinas. Many of those rejecting these categories are doing so because they fail to see their consistency with Scripture, arguing that these various distinctions or metaphysical conclusions are not found in scripture, nor were they addressed by the authors of scripture. This has led some to deny eternal generation, divine simplicity (as is classically and confessionally articulated), and to positively affirm the eternal subordination of the Son.

Although those who would affirm these doctrines are not anti-Trinitarian, and seek to defend the deity of Christ, there is no doubt that many of the arguments made by those desiring to uphold Biblical beliefs are making arguments that sound strikingly similar to the Socinians. Neo-Socinian thought rejects Aristotelian categories, for the same reasons that Socinus and Crell did. Even though the intentions may be praiseworthy (such as seeking to be thoroughly biblical), it is dangerous to throw out the teachings of the church's Great Tradition or the Reformed confessions, just because one cannot find a particular verse that says such. Wisdom encourages us instead to search the paths of old, and to join with those who have confessed the same faith for centuries.

Derrick Brite serves as pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Aliceville, Alabama. He received his MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary in Atlanta and is currently pursuing a PhD in systematic theology at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Related Links

"How Is the Trinity Vital for My Christian Life?" by Danny Hyde

"Francis Turretin on Fundamental Articles" by Ryan McGraw

The Holy Trinity: Revised and Expanded by Robert Letham

Notes

[1] Sarah Mortimer, Reason and Religion in the English Revolution: The Challenge of Socinianism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 13-14.

[2] William Cunningham, Historical Theology, Vol. 2: A Review of the Principal Doctrinal Discussions in the Christian Church Since the Apostolic Age (Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, repr. 1994), 155.

[3] Ibid., 161.

[4] Mortimer, Reason and Religion, 149.

[5] Ibid., 150-151.

[6] Cunningham, Historical Theology, 161.

[7] Mortimer, Reason and Religion, 152.

[8] Ibid., 155.

[9] This term isn’t new, but I first encountered it in James Buchanan, The Doctrine of Justification: An Outline of Its History in the Church and of Its Exposition from Scripture (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1867), 184.