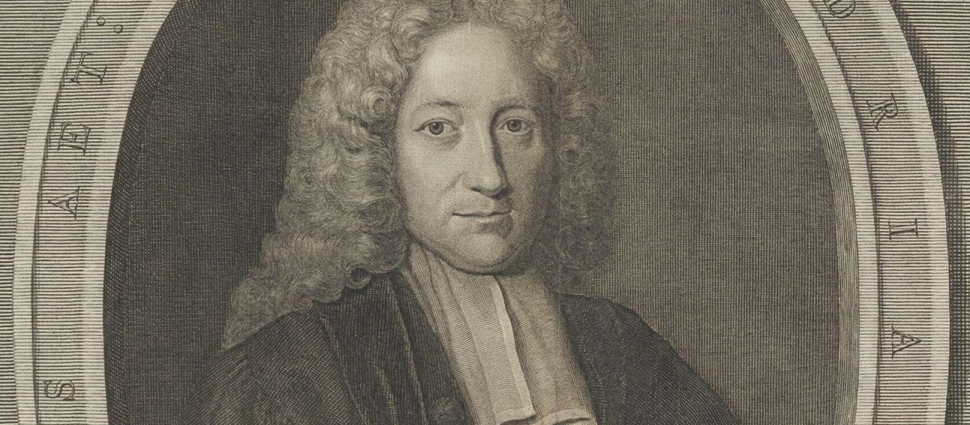

Adriaan Reland – A Scholar for God’s Glory

Adriaan Reland – A Scholar for God’s Glory

In academic circles, Adriaan Reland is hailed as a remarkable Orientalist and linguist whose studies and writings have contributed to dispel many prejudiced views of his time. What most sources ignore, however, is his motivation.

Born in 1676 in the small village of De Rijp, in North Holland, to a Protestant minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, Reland never forgot the reason for his work and studies. “My labors shall make way for others for the triumph of the truth and the evangelical faith and the ultimate aim of our actions, the glory of the only and one God, Father, Son, and Spirit,”[1] he wrote.

Excelling in his studies, he entered the University of Uthrecht at age 14 and completed his doctorate in 1699. Two years later, his interest and proficiency in Hebrew, Syriac, and Arabic led to his appointment as Professor of Oriental Languages at the University of Utrecht. This gave him an opportunity to continue his study in a wide range of Asian languages, including Malay (although the university itself didn’t have hardly any original text).

Reland’s Influence on Missions to Muslim Countries

Reland completed his main work, De religione Mohammedica libri duo, in 1705 (and extended it in 1717). His motivation was similar to what had moved the famous theologian Gisbert Voetius and his pupil Johannes Hoornbeek to launch heartfelt appeals to western scholars to correct their “coarse ignorance about Mohammedism,” pleading for a study of Arabic in order to truly understand the Qur’an. This was particularly important for Dutch missionaries that had moved to Muslim areas of Southeast Asia. Reland repeated this exhortation, adding that some of the prejudices typical of his age had seeped into the Latin translations.

While firmly convinced of the exclusive truth of the Bible, Reland contended, with rare objectivity for his times, that religions should be examined impartially through a study of their authentic documents and not through the writings of their detractors (he reminded his Protestant readers of the unfounded accusations Roman Catholics had published against them).

In fact, after summarizing Islamic teachings for his readers, he corrected 39 myths commonly believed about Muslims. Following Voetius, he suggested that missionaries should begin their dialogue with Muslims by highlighting what they had in common before moving on to an examination of passages where the Qur’an departed from the Old Testament and New Testament Scriptures that Muslims claim to recognize.

He also pointed out, as others did before him, that Islam is a rational religion (a reason, in his view, for his rapid diffusion). In fact, it seems more rational and in accord with the laws of nature than the Bible, which includes mysteries such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Resurrection. Reland believed that this realization would help missionaries to understand the Islamic attraction and to better interact with Muslims.

Reland’s acknowledgement of the rationality of Islam was not meant to be an endorsement. A staunch defender of orthodox Christianity, he was opposed to any form of religion that tried to bind God within the limits of human reason. He was particularly opposed to any form of Pelagianism, which he described as “an error so natural to corrupt man that, tho there is none more powerfully withstood and oppos’d in Scripture, yet it has commonly been the most universal of all heresies,” leading “directly to the doctrine of the Unitarians.” (Muslims called themselves “unitarians,” as opposed to Christians, whom they called “associants,” and many European Unitarians quoted the Qur’an in defense of their views).

“So soon as man is enamour’d with himself, and puts himself in the place of God,” Reland wrote, “he perverts all the truths of Chrtistianity, and forms to himself a religion perfectly human, more like the moral philosophy of the Pagans, than the doctrine of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ.”[2]

In his Preface to De religione Mohammedica, Reland declared that he was only interested in the truth (“Truth, whatever it is, should be searched after”). He concluded the Preface with a disclaimer: “Although I have sometimes spoke very freely, yet I had no manner of design to give offense to any sort of persons. Nay, I have suppressed several remarks, that very naturally offer’d themselves, and laid them aside, because they seemed odious and personal, and consequently apt to displease persons whom I had no mind to put out of humour. If, notwithstanding this, it should happen that, contrary to my intentions, any person takes offense, I should be very sorry for it. But having advanced nothing but what is built on good proofs and, besides, having acted from no motive of hatred or grudg, I shall easily comfort myself upon the testimony of my conscience.”[3]

Reland’s De religione Mohammedica was translated into Dutch, French, German, English, and Spanish. The Roman Catholic Church placed it in the list of forbidden books in 1722.

Reland never traveled outside of his country, but corresponded with scholars, publishers, missionaries, and officials of the Dutch East India Company. He was also a cartographer, producing impressive maps of Palestine, Persia, Japan, and Southeast Asia; and a poet (his Galatea. Lusus poeticus, a small collection of thirteen love elegies, received high praises). His interests included biblical archeology and numismatics.

Reland’s work left a tremendous contribution to missionary work to Muslim countries. Modern authors agree that his writings, while firmly founded in Christian orthodoxy, have contributed to foster a balanced view of Islam among scholars, missionaries, and the general public – thus facilitating a peaceable and informed discussion.

[1] Adriaan Reland, De religione Mohammedica libri duo. Editio altera auctior, Utrecht, Willem Broedelet, 1717, quoted in Charles H. Parker, “Better the Turk than the Pope: Calvinist Engagement with Islam in Southeast Asia,” in Protestant Empires: Globalizing the Reformation, ed. Ulinka Rublack, Cambridge University Press, 2020, 192.

[2] Adriaan Reland, Four Treatises Concerning the Doctrine, Discipline and Worship of the Mahometans, London, 1712, 157

[3] Ibid., 160